Almost every application needs to keep track of its own state, regardless of what it otherwise does. This typically includes:

- Sizes and locations of movable/resizable elements of the UI

- Last entered data (e.g. username)

- Settings and user preferences

A common approach is to store this data in a .settings file, and read and update it as needed. This involves writing a lot of boilerplate code to copy that data back and forth. This code is generally tedious, error prone and no fun to write.

Jot takes a different, declarative approach: Instead of writing code that copies data back and forth, you declare which properties of which objects you want to track, and when to persist and apply data. This is a more apropriate abstraction for this requirement, and results in more concise code, as demonstrated by the example.

The library starts off with reasonable defaults for everything but it gives the developer full control over when, how and where each piece of data will be stored and applied.

Jot is available on NuGet and can be installed in the usual way:

install-package Jot

To illustrate the basic idea, let's compare two ways of dealing with this requirement: .settings file (Scenario A) versus Jot (Scenario B).

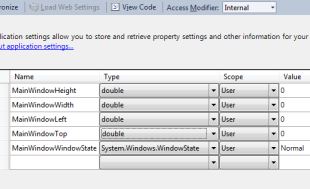

Step 1: define settings

Step 2: Apply previously stored data

public MainWindow()

{

InitializeComponent();

this.Left = MySettings.Default.MainWindowLeft;

this.Top = MySettings.Default.MainWindowTop;

this.Width = MySettings.Default.MainWindowWidth;

this.Height = MySettings.Default.MainWindowHeight;

this.WindowState = MySettings.Default.MainWindowWindowState;

} Step 3: Persist updated data before the window is closed

protected override void OnClosed(EventArgs e)

{

MySettings.Default.MainWindowLeft = this.Left;

MySettings.Default.MainWindowTop = this.Top;

MySettings.Default.MainWindowWidth = this.Width;

MySettings.Default.MainWindowHeight = this.Height;

MySettings.Default.MainWindowWindowState = this.WindowState;

MySettings.Default.Save();

base.OnClosed(e);

} This is quite a bit of work, even for a single window. If we had 10 resizable/movable elements of the UI, the settings file would quickly become a jungle of similarly named properties. This would make writing this code quite tedious and error prone.

Also notice how many times we mention each property - a total of 5 times (e.g. do a Ctrl+F Left, and don't forget to count the one in the settings file image).

Step 1: Create a StateTracker instance and expose it to the rest of the application (for simplicity's sake, let's expose it as a static property)

static class Services

{

public static StateTracker Tracker = new StateTracker();

}Step 2: Set up tracking

public MainWindow()

{

InitializeComponent();

Services.Tracker.Configure(this)//the object to track

.IdenitifyAs("main window")//a string by which to identify the target object

.AddProperties<Window>(w => w.Height, w => w.Width, w => w.Top, w => w.Left, w => w.WindowState)//properties to track

.RegisterPersistTrigger(nameof(SizeChanged))//when to persist data to the store

.Apply();//apply any previously stored data

}That's it. It's concise, the intent is clear, and there's no repetition. Notice that we've mentioned each property only once, and it would be trivial to track additional properties.

The above code (both scenarios) would work for most cases, but for real world use we would need to handle a few more edge cases, and since tracking a Window or Form is so common, Jot already comes with pre-built settings for them, so we can actually track a window with a single line of code:

Step 2 (revisited)

public MainWindow()

{

InitializeComponent();

//Why SourceInitialized?

//Subtle WPF issue: WPF will always maximize a window to the primary screen

//if WindowState is set too early (e.g. in the constructor), even

//if the Left property says it should be on the 2nd screen. Setting

//these values in SourceInitialized resolves the issue.

this.SourceInitialized += (s,e) => Services.Tracker.Configure(this).Apply();

}The pre-built settings for Window objects are defined in WindowConfigurationInitializer. During the Configure method, the WindowConfigurationInitializer object will set up tracking for Hight, Width, Top, Left and WindowState properties of the window, along with some validation for edge cases. We can replace the default way Jot tracks Window objects by supplying our own ConfigurationInitializer for the Window type, more on that later.

The StateTracker class has an empty constructor which uses reasonable defaults, but the main constructor allows you to specify exactly where the data will be stored and when:

StateTracker(IStoreFactory storeFactory, ITriggerPersist persistTrigger)The two arguments are explained below.

The storeFactory argument controls where data is stored. This factory will be used to create a data store for each tracked object.

You can, of course, provide your own storage mechanism (by implementing IStore and IStoreFactory) and Jot will happily use it.

By default, Jot stores data in .json files in the following folder: %AppData%\[company name]\[application name] (company name and application name are read from the entry assembly's attributes). The default folder is a per-user folder, but you can use a per-machine folder like so:

var tracker = new StateTracker() { StoreFactory = new JsonFileStoreFactory(false) };//true: per-user, false: per-machineOr you can specify a folder path:

var tracker = new StateTracker() { StoreFactory = new JsonFileStoreFactory(@"c:\example\path\") };For desktop applications, the per-user default is usually fine.

The StateTracker uses an object that implements ITriggerPersist to get notified when it should do a global save of all data. The ITriggerPersist interface has just one member: the PersistRequired event.

The only built-in implementation of this interface is the DesktopPersistTrigger class which fires the PersistRequired event when the (desktop) application is about to shut down.

Note: Objects that don't survive until application shutdown should be persisted earlier. This can be done by specifying the persist trigger (

RegisterPersistTrigger) or by explicitly callingPersist()on theirTrackingConfigurationobject when appropriate.

Since Jot doesn't know anything about our objects, we need to introduce them and tell Jot which properties of which object we want to track. For each object we track, a TrackingConfiguration object will be created. This configuration object will control how the target object is tracked.

There are 4 ways of initializing TrackingConfiguration objects, each being advantageous in certain scenarios.

Here they are...

To control how a single target object is tracked, we can manipulate its TrackingConfiguration directly. For example:

tracker.Configure(target)

.IdentifyAs("some id")

.AddProperties(nameof(target.Property1), nameof(target.Property2))

.RegisterPersistTrigger(nameof(target.PropertyChanged))Once we've set up the configuration object, we can apply any previously stored data to its tracked properties by calling Apply() on the configuration object.

With configuration initializers, we can configure tracking for all instances of a given (base) type, even if we don't own the code of that type.

Say we want to track all TabControl objects in our application in the same way:

- Track only the

SelectedIndexproperty - Persist when

SelectedIndexChangedevent fires

Here's how to create a default configuration for tracking all TabControl objects:

public class TabControlCfgInitializer : IConfigurationInitializer

{

public Type ForType

{

get

{

return typeof(TabControl);

}

}

public void InitializeConfiguration(TrackingConfiguration configuration)

{

configuration

.AddProperties(nameof(TabControl.SelectedIndex))

.RegisterPersistTrigger(nameof(TabControl.SelectedIndexChanged));

}

}We can register it like so:

_tracker.RegisterConfigurationInitializer(new TabControlCfgInitializer());With our initializer registered, the StateTracker can use it to set up tracking for TabControl objects, without us having to repeat the configuration for every TabControl instance. To track a TabControl object now, all we need to do is:

_tracker.Configure(tabControl1).Apply();Jot comes with several configuration initializers built-in:

- WindowConfigurationInitializer (for

Window) - FormConfigurationInitializer (for

Form) - DefaultConfigurationInitializer (enables the use of

[Trackable]attributes andITrackingAwarefor all objects)

You can access and manipulate the registered configuration initializers via the tracker.ConfigurationInitializers property.

public class GeneralSettings

{

[Trackable]

public int Property1 { get; set; }

[Trackable]

public string Property2 { get; set; }

[Trackable]

public SomeComplexType Property3 { get; set; }

}With this approach, the class is self-descriptive about tracking. Now all that's needed to start tracking an instance of this class is:

tracker.Configure(settingsObj).Apply();public class GeneralSettings : ITrackingAware

{

public int Property1 { get; set; }

public string Property2 { get; set; }

public SomeComplexType Property3 { get; set; }

public void InitConfiguration(TrackingConfiguration configuration)

{

configuration.AddProperties<GeneralSettings>(s => s.Property1, s => s.Property2, s => s.Property3);

}

}The class is now self-descriptive about tracking, just like with the attributes approach. In this case, it manipulates its tracking configuration directly, which is a bit more flexible compared to using attributes.

All that's needed now to start tracking an instance of this class is to call:

tracker.Configure(settingsObj).Apply();Now, here's the really cool part.

When using an IOC container, many objects in the application will be created by the container. This gives us an opportunity to automatically track all created objects by hooking into the container.

For example, with SimpleInjector we can do this quite easily, with a single line of code:

var stateTracker = new Jot.StateTracker();

var container = new SimpleInjector.Container();

//configure tracking and apply previously stored data to all created objects

container.RegisterInitializer(d => { stateTracker.Configure(d.Instance).Apply(); }, cx => true);Since the container doesn't know how to set up tracking for specific types, we need to specify the configurations in one or more of the following ways:

- using configuration initializers

- using

[Trackable]and[TrackingKey]attributes - implementing

ITrackingAware

To summarize what this means: with the above few lines of code in place, we can now track any property of any object just by putting a [Trackable] attribute on it! Pretty neat, huh?

Each tracked object will have its own file where its tracked property values will be saved. Here's an example:

The file name includes the type of the tracked object and the identifier: [targetObjectType]_[identifier].json.

We can see, we're tracking three objects: AppSettings (id: not specified), MainWindow (id: myWindow) and a single TabControl (id: tabControl).

Demo projects are included in the repository. Playing around with them should be enough to get you started.

You can contribute to this project in the usual way:

- First of all, don't forget to star the project

- Fork the project

- Push your commits to your fork

- Make a pull request

Jot can be found on:

- Nuget: https://www.nuget.org/packages/Jot

- Codeproject: http://www.codeproject.com/Articles/475498/Easier-NET-settings (old but still mostly relevant)

- Web application scenarios