| layout | title | description |

|---|---|---|

default |

Beginners Track - Understanding Docker Underlying Technology |

collabnix | DockerLab | Docker - Beginners Track |

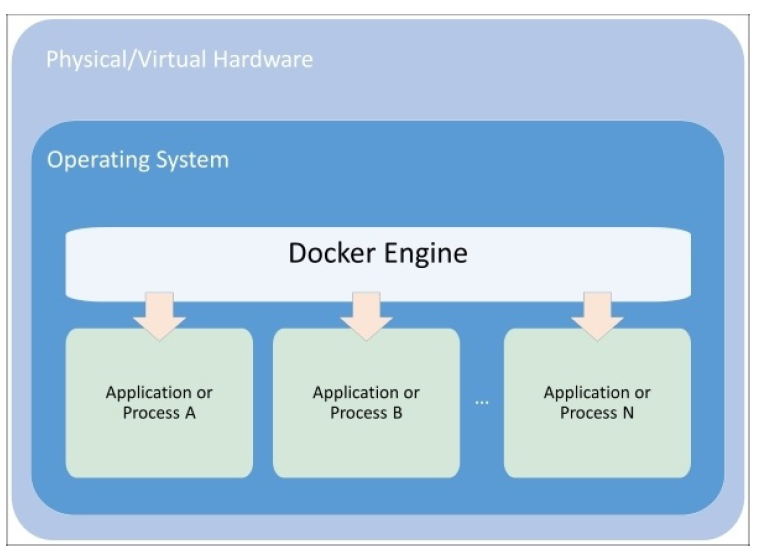

To understand Docker underlying technology, let us first understand the core container technology.

At the core of container technology are cGroups and namespaces. Additionally, Docker uses union file systems(UFS) for added benefits to the container development process. Control groups (cGroups) work by allowing the host to share and also limit the resources each process or container can consume. This is important for both, resource utilization and security, as it prevents denial-of-service attacks on the host’s hardware resources. Several containers can share CPU and memory while staying within the predefined constraints.

Namespaces offer another form of isolation in the way of processes. Processes are limited to see only the process ID in the same namespace. Namespaces from other system processes would not be accessible from a container process. For example, a network namespace would isolate access to the network interfaces and configuration, which allows the separation of network interfaces, routes, and firewall rules.

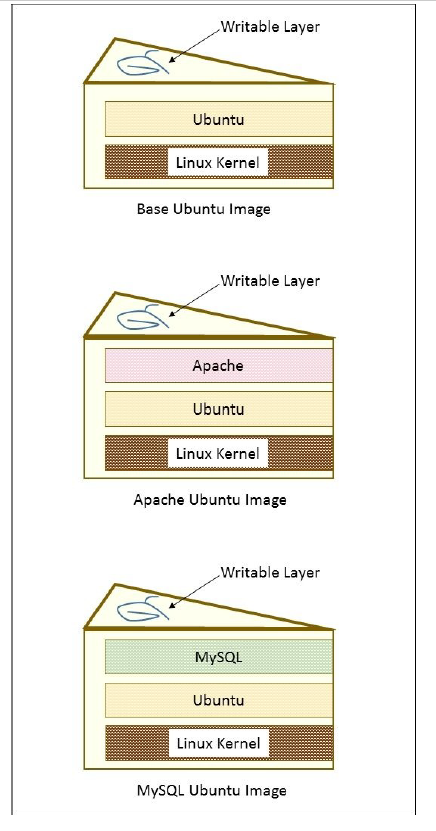

Union file systems are also a key advantage to using Docker containers. The easiest way to understand union file systems is to think of them like a layer cake with each layer baked independently. The Linux kernel is our base layer; then, we might add an OS like Red Hat Linux or Ubuntu. Next, we might add an application like Nginx or Apache. Every change creates a new layer. Finally, as you make changes and new layers are added, you’ll always have a top layer (think frosting) that is a writable layer.

What makes this truly efficient is that Docker caches the layers the first time we build them. So, let’s say that we have an image with Ubuntu and then add Apache and build the image. Next, we build MySQL with Ubuntu as the base. The second build will be much faster because the Ubuntu layer is already cached. Essentially, our chocolate and vanilla layers, from Figure 1.2, are already baked. We simply need to bake the pistachio (MySQL) layer, assemble, and add the icing (writable layer).

Proceed >> Can container communication cross over to noncontainerized apps?